- Home

- Miriam Karmel

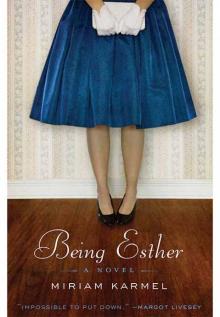

Being Esther Page 6

Being Esther Read online

Page 6

“We couldn’t do this when we were teenagers, Essie.”

“Who had cars?” she said, then kissed him back.

After Ceely leaves, Esther dumps the cereal into the garbage and rinses out the bowl. Then, as she crosses to the refrigerator, she imagines hearing Marty’s critical voice. How many times had he warned her? “That’s the first place burglars look.”

It’s as good as any, she thinks, as she opens the freezer door.

Yet as she reaches into the back of the freezer she pauses, afraid that her husband was right. But then her hand finds it. It’s there. She pulls out the ice cream carton and sighs, satisfied that no burglar would ever think to look here.

She shuffles to the table, holding the carton as if it were filled with quails’ eggs. She sets it down, pauses. Still spooked by her husband’s ghost, she glances quickly over her shoulder, then chides herself for being ridiculous. Gingerly, she lifts the lid. The ring is there. A star sapphire. A gift from Marty the year he lost his way. “Men stray,” her mother had said, as if she were reporting some immutable law—gravity, relativity, the orbit of the planets around the sun. Esther has never felt comfortable wearing the ring.

The pearls are there, too. She fingers the strand, recalling how they’d looked around her mother’s neck, the way they rested just above the cleavage that she didn’t try to conceal.

She fishes out the keys. They’re cold. She wraps her hand around them and squeezes hard, relishing the feeling as they dig into her flesh. She squeezes harder, until the cold metal cuts into her, awakening her senses, like pinching herself to be sure she isn’t dreaming.

One morning, while Esther is reading the obituaries, Ceely phones to say she’s running out to the supermarket. “I don’t need a thing,” Esther says. “I’m going to the desert.”

“The desert!” Ceely has a way of repeating Esther’s statements as if she were pacifying a child with an overactive imagination. “The desert.” She whistles.

“You’d think I just announced a trip to the moon,” Esther snaps. She straightens the edges of the newspaper, which is spread out on the table before her. “I want to see the desert. Once more.” Her voice trails off. “Before I die.”

Ceely sighs impatiently. “You’re not dying.”

“Then why are you pushing me into that place?”

Impatiently, Ceely says, “It’s not a dying place. And I’m not pushing you.” She pauses. “It will be easier,” she says, her voice softening. “That’s all.”

“Easier than what? Easier for whom?”

“Why do you do this?” Ceely whines, her voice rising.

“Do what?”

“Twist everything.” Now she is shouting.

“Nobody lives forever,” Esther declares, slapping her hand on the newspaper. Then she begins reading aloud from the obituaries, like the rabbi intoning the names of the dead before reciting the mourner’s Kaddish. When she is finished, she says, “I’m off to the desert. Four nights at the Doubletree Inn. Plus a day trip to Mexico. A bus picks you up at the hotel.” With each assertion, the lie blooms. Had she known how easy it was, she might have started lying sooner.

“I’m going with you,” Ceely blurts.

“Maybe I don’t want you to go,” Esther says, quickly regretting the careless remark.

“How can you not want me to go?” Ceely is whining again, the way she did when Esther imposed a ten o’clock curfew.

“I don’t need a babysitter,” Esther says, sitting taller in her chair. “And besides.” She pauses. “You can be unpleasant.” She presses the newspaper with her hand, which is so contorted she appears to be clawing the pages. Frightened by her body’s insubordination, by her inability to direct it as she wishes, she dismisses the offending hand, sending it straight to her lap. Then she hears herself saying, “Do you really want to go?” But before Ceely can reply, Esther says, “Good. Then it’s settled.”

Esther makes all the arrangements. She wants to visit the Desert Museum and a place where they reenact the gunfight at the O.K. Corral. She wants to ride the tram in Sabino Canyon and behold the giant saguaro. She has read about the best place for margaritas. She hopes green corn tamales will be in season. And she signs up for a day trip to Mexico.

The bus for the trip to Nogales picks them up at their hotel after breakfast. Four people have boarded by the time Ceely and Esther get on. An older couple, sporting baseball caps and fanny packs, are seated toward the front. Water bottles in mesh holders dangle from their necks. They remind Esther of the smiling couple on the Cedar Shores brochure. Seated behind them is a pair of older women who could easily be Esther and Lorraine. At the next two hotels, six more people get on, all of them considerably older than Ceely.

The driver pulls into a McDonald’s parking lot about two hundred yards from the border, and before the passengers disembark, he hands out maps of the Nogales business district. Then he holds up a map and with his finger, traces a route from the border crossing to Calle de Obregon, the street where all the pharmacies are clustered. “Hey!” The man with the water bottle interrupts. “I thought you’re supposed to be our guide.”

Esther elbows Ceely in the ribs and through clenched teeth whispers, “Don’t make trouble.” For Esther, survival has always depended on blending in, as if the next pogrom were about to sweep through the village and her only hope was to lay low. No coughing, no sneezing; not a peep until the marauders take off. This instinct is as ingrained in Esther as if she’d been born not in Chicago but in the Polish shtetl from which her parents had fled a lifetime ago. So while the rest of the group murmurs agreement with the provocateur, as the chorus of dissent swells, Esther’s elbow remains firmly lodged in her daughter’s ribs.

“But we signed up for a tour,” the man persists.

The driver stares the group down and waving the map, says, “This is the tour. So listen up.”

At the frontera, they push through a metal turnstile, and though Esther has traveled to Mexico many times in the past, she has never walked across the border. Entering the country is as easy as passing through a revolving door. “Mexico!” she cries triumphantly and waves her cane in the air, as if she has just circumnavigated the globe and is staking her claim to the New World.

Despite the fact that she is traveling with a cane (at Ceely’s insistence), Esther leans on her daughter for support, and Ceely doesn’t resist. Arm in arm they make their way along the rutted sidewalk. They pass women crouched against dusty stucco walls, clutching babies in one arm while reaching out with the other in a gesture of permanent supplication. They pass vendors selling their wares from blankets spread out on the gritty sidewalks. Other vendors carry merchandise in trays yoked around their necks with colorful woven straps. The more prosperous merchants hawk their goods from the narrow doorways of cinder-block shops. They scrape and bow, feigning respect for the women. In sing-song English, they call out, urging them to enter. “Enter!” they cry. “Take a look. Is cheaper than K-Mart.”

“Don’t look,” Ceely whispers, pulling Esther closer.

The two women stroll past one store after another, their wares spilling out onto the sidewalk: piñatas, papier maché avocados, a lotion purportedly made from the sebaceous glands of giant sea turtles. They continue on, as if the real Nogales will present itself around the corner or on the next block. All the while, Ceely reins Esther in as the mocking cries trail after them. “How much you want to pay? How much? It’s free! Lady, for you, it’s free.”

Suddenly Esther stops. “I think we’re lost,” she declares as she rummages through her straw bag for the map. She and Ceely are consulting it when a man approaches and offers to take their picture. He is short and wiry, with a pencil-thin mustache and jet-black hair slicked down and parted in the middle.

Esther looks up, smiles at him, and with an air of disbelief says, “How nice. You want to take our picture?”

“No!” Ceely cries. Then contritely, she says, “No, gracias,” as she stalks off, p

ulling Esther with her.

Undeterred, the man cries out, “Real cheap!”

“Cuanto?” Esther calls back, as she breaks away from Ceely.

“Cheaper than K-Mart!”

“How much?” Esther holds a hand to her ear as she approaches the man, pretending she hadn’t heard. By then, she is making full eye contact, as she prepares to strike a deal with the photographer.

Ceely, meanwhile, is approached by a young girl selling brilliantly colored plastic sticks that bloom from a straw basket like a bouquet of meadow flowers. The girl’s creamy skin is the color of café con leche. A pink headband holds her silky black hair in place. Tiny gold earrings glint from her delicate lobes. Somebody has fussed over her. “The same somebody,” Ceely later tells Esther, “who sent her into the streets to peddle plastic backscratchers.” By the time Ceely plucks a red stick from the basket, the photographer is guiding Esther onto an inverted plastic milk crate and hoisting her onto a burro.

The poor beast is dressed in a sun-bleached serape, velvet sombrero, and embroidered blinders. Despite the heat, or perhaps because of it, he stands uncomplaining, head bowed, as if hoping not to draw attention to the shame of being dressed like a caricature of a tarted-up beast of burden.

Meanwhile, his master is holding out a velvet sombrero to Esther, gesturing for her to put it on, but she shakes her head and points to her own floppy-brimmed straw hat. It is a playful hat, and together with her white linen slacks and blue striped silk blouse, Esther conveys an easy sense of style. “Hop up!” she calls to Ceely, who is standing in the distance examining her new purchase.

Ceely protests, but Esther insists, and before she knows it the man is gently pushing her up beside her mother. Then he skitters to his camera, an ancient Polaroid mounted on a tripod and covered with a black cloth, giving it the air of a far more elaborate piece of equipment. He sticks his head under the cloth, then pops back out, fingers pressed to the corners of his mouth, pantomiming a smile. After ducking back under, he directs the women with an upheld hand and a high-pitched, syncopated whistle. “Okay!” he cries, and clicks the shutter.

As they head down the street, Esther tells Ceely she’s always wanted to do that.

Bemused, Ceely says, “Have your picture taken on the back of a burro?”

“Hmmm,” Esther says, dreamily.

Again, they are consulting the map, for Esther is determined to find Calle de Obregon. “Maybe we should ask someone,” she is saying to Ceely, when another man approaches, this one bearing a tray of wristwatches.

“Oh, here we go again,” Ceely mutters, as she tries moving her mother along.

But Esther digs in her heels. Something about the way the tray hangs from the man’s neck reminds her of the long-legged girls who once moved among the tables in nightclubs, selling cigarettes and mints. Quickly seizing on Esther’s hesitation, the man plucks a silver watch from his tray and holds it up till it catches the sun and glints like gaudy fishing lure.

“No gracias,” Ceely says, as she tugs at her mother’s elbow. “No gracias.” But Esther refuses to budge.

Esther, who speaks pidgin Spanish, Spanglish, a Spanish without verbs, is nevertheless fluent in the art of the deal. She frowns and shakes her head each time the man selects a watch from his battered tray. At last she nods at a watch that looks very much like all the ones she’s rejected. The man, beaming, motions for her to try it on. After great confusion over the cane, which she finally crooks over her right arm, he gently fastens the silver band around her left wrist. The two of them trade polite smiles as she holds out her arm and admires the timepiece.

Gingerly, with the help of her cane, Esther makes her way back toward Ceely, who is waiting at the end of the block. “Seiko!” she cries, waving her wrist in the air.

“Fake-o,” Ceely snorts, as Esther sidles up to her.

Esther gives her daughter a baleful look. “Ten dollars. Not bad, huh?”

“Not bad,” Ceely agrees.

They are walking past the duty-free shop on the Arizona side of the border when Esther says, “Let’s go in.”

Ceely balks and Esther, tapping her new watch, indicates they have plenty of time.

Over the years, Esther has purchased, in airport duty-free shops, Belgian chocolates, French perfumes, cloying after-dinner liqueurs. Once, at thirty thousand feet over the Atlantic, she purchased a strand of Japanese freshwater pearls. Always, upon exiting the plane, smiling flight attendants presented these purchases as if they were gifts.

Now on the American side of the border, Esther purchases a bottle of Johnnie Walker Black Label and a tube of red lipstick, but instead of being greeted by a perky flight attendant she is stopped at the door by a short, round woman dressed, not unlike a park ranger, in olive drab. Holding up her hand, the officious woman orders Esther to stop, then points to a cluster of people all clutching plastic bags similar to the one Esther is holding. “Over there,” she commands. “Stand over there.”

“I don’t understand,” Esther says.

“What don’t you understand?”

“Why you want me over there.”

“You want duty free?” Then she explains that Esther must reenter Mexico, go through customs, and declare her purchases. “Then you can keep whatever is in that bag.”

“But we have a bus to catch.” Esther motions vaguely in the direction of the McDonald’s.

The woman shrugs. “Not until you go through customs.”

“But the driver.” Esther’s voice trails off as she points her cane to indicate where he might be. “He won’t wait.”

The woman, whose job it is to shepherd customers to the border where she can be sure they cross back into Mexico, in some bizarre circumvention of international law, gives Esther a withering look and again points to the group.

“Look what you’ve gotten us into,” Ceely hisses as she pulls her mother aside.

In a voice intended to carry, Esther says, “She won’t listen to reason.” Glaring at the woman, she tells Ceely, “Nobody said anything about returning to Mexico. It’s the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever heard.”

“You didn’t think you’d get duty free for nothing?”

“You sound like my father,” Esther frowns. “No lunch is for free, Esther. How many times did I hear that?”

“Well, Poppy had a point.”

A point? What was the point? That Esther wasn’t good enough, deserving enough of life’s little perks? It occurs to her now, as she clutches the bag, that she’s gone through life saying no thank you to second helpings, and denying herself all the trimmings. Others got the drumstick, the cherry on the sundae, while Esther politely held back, lest she be accused of trying to get something for nothing.

Vexed, Esther says, “Please, Ceely. Don’t start with me.”

“I shouldn’t start? You’re the one who got us into this. Now we’re going to miss the bus.” With a nod toward the woman, Ceely says. “You realize, she hates us.”

“Don’t be ridiculous!”

“She does. You can tell,” Ceely insists. “She thinks we’re greedy Americans. Stupid gringos.”

“How do you know what she thinks?”

“Besides, how many bargains do you need?” Ceely rattles a bag full of purchases Esther made after lunch: Prozac, Ambien, Lipitor, Retin-A, Trusopt, Valium. She complains that Esther had tricked her into going on a drug run. “You told me you wanted to see the desert.”

“I do. I did. We did,” Esther insists. “What do you think we drove through on the bus?”

Ceely gives her mother a baleful look and Esther lectures her daughter on the perfidies of the drug companies. “Big Pharma,” she says. “Big Pharma keeps prices so high that people cut their prescriptions in half or go without food to pay for their drugs. Big Pharma lies about clinical trials, suppressing questionable results.”

“You’re beginning to sound like a talk radio nut,” Ceely says.

“And the government’s in on it,” Esther

says, with finality.

“But you don’t even take these,” Ceely says.

“Some are for gifts.”

“Gifts?” Ceely moans.

“Look!” Esther cries. “Look who’s here.”

“Please don’t change the subject,” Ceely whines.

“The couple.” Esther points with her cane. “From the bus.” Leaning closer, she whispers, “The ones with the water bottles. Over there, by the Swiss Army knives. Wouldn’t you know it.” She waves her cane again. “Hello,” she calls from across the aisle.

They smile and wave back.

“I would have figured you have plenty of those already,” Esther cries out.

“Christmas presents.” The man beams.

“What a great idea. But remember not to take them on the plane. My daughter had one confiscated at security,” Esther says, nodding toward Ceely. “They called it contraband. Contraband! Can you believe it? She looks like a terrorist, don’t you agree?”

“Ma,” Ceely tugs at Esther’s sleeve. “You’re shouting.”

“Oh, what difference does it make?” Esther pulls away.

Then it’s Ceely’s turn to point and exclaim. “Look! They’re leaving.”

The woman masquerading as a park ranger is addressing the group.

“Then get going.” Esther takes the drugs from Ceely, trading them for the bag with the lipstick and the scotch. Gently, she pushes her daughter toward the group.

Ceely looks confused. “What do you expect me to do with these?”

“You’ll go.”

“Where?”

“With the woman.”

“The coyote?” Ceely snorts. “She isn’t sneaking me across the border. These are yours.” She tries pushing the bag back into Esther’s hands, but Esther resists. “You’re making a scene,” she hisses.

“I’m not going.” Ceely sounds petulant, like the three-year-old who’d stomped her foot whenever she didn’t get her way.

Being Esther

Being Esther